Amorphous solid dispersions play an essential role in modern pharmaceutical research. They improve the solubility and dissolution rate of poorly water-soluble drugs, and therefore they gain more importance in drug development. Although several approaches exist, each method shows clear benefits but also some challenges. As a result, it is necessary to examine amorphous solid dispersions in a broader scientific context. For a detailed overview, Thomas Rades and Keita Kondo [Rades_2022] present valuable insights into the fundamentals and latest findings. In addition, recent studies highlight CELLETS® 175, microcrystalline cellulose spheres, as a promising solution. These MCC spheres act as drug carriers and, due to their excellent friability, also function as milling balls. Consequently, they create new opportunities for drug formulation. Moreover, MCC starter beads expand these applications even further. Researchers who want to test this approach can request material samples before exploring the work of Rades and colleagues in more detail.

Draw-back on Amorphous solid dispersions

Amorphization is a promising way to improve solubility and dissolution of poorly water-soluble drugs. Amorphous solids lack a crystal lattice with long-range order [1]. However, amorphous forms remain thermodynamically unstable because their chemical potential is higher than in crystalline forms. As a result, amorphous drugs often show low physical stability and eventually recrystallize [2], [3]. Therefore, stabilizing strategies are crucial in the development of amorphous products. These strategies include amorphous solid dispersions (ASDs) [4], [5] and co-amorphous formulations [6], [7], [8].

ASDs are the most widely used method to prepare amorphous products. They involve glass formation by dispersing drug molecules into an amorphous polymer [4], [5]. Nevertheless, ASD systems often need a large amount of polymer to stabilize the drug, since miscibility between drug and polymer is low [9]. This requirement leads to a high bulk volume of the final product.

In contrast, co-amorphous systems have gained attention as an alternative. They create a single amorphous phase in which multiple low molecular weight compounds, including drugs, mix uniformly at the molecular level [6], [7], [8]. Moreover, co-amorphous mixtures usually provide both higher physical stability and improved dissolution [6], [7], [10].

drug-drug combinations and drug-excipient mixtures

Co-amorphous systems usually fall into two groups: drug-drug combinations and drug-excipient mixtures. In drug-drug combinations, two drug compounds form an amorphous phase. They stabilize each other through intermolecular interactions [11], [12], [13]. These systems can provide combined therapeutic effects. However, their use remains limited. Not all drug-drug pairs are suitable for combination therapy, and fixed dosing often restricts their application to co-amorphization.

In contrast, drug-excipient systems use low molecular-weight substances as co-formers. These include organic acids [14], sugars [15], and amino acids [16]. Their properties and the mixing ratio with the drug strongly influence both dissolution and physical stability [8], [10]. Recently, researchers systematically studied different combinations of drugs with amino acids [17], [18]. The results showed that well-chosen amino acids can improve dissolution and stability. For example, acidic drugs combined with basic amino acids often create strong interactions. Thus, amino acids emerge as a highly promising class of co-formers for co-amorphous formulations.

Amorphous solid dispersions: Co-amorphous mixtures

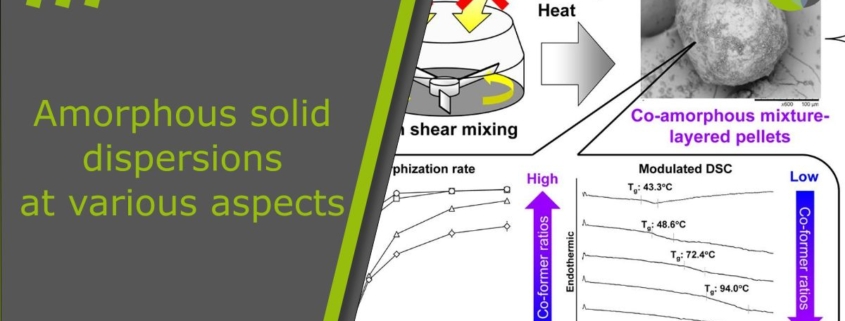

Co-amorphous mixtures have been prepared using melt quenching [13], [19], spray drying [20], [21], and ball milling [16], [22]. The resulting solids appear as cakes or powders regardless of the method. Therefore, downstream processes such as milling and granulation are usually necessary to obtain final dosage forms like capsules or tablets for oral use [23]. However, these additional steps often increase the risk of phase separation and crystallization because of moisture, thermal stress, and mechanical stress.

In amorphous solid dispersion (ASD) systems, researchers developed one-step preparation methods to avoid these issues. For example, ASD granules have been produced by amorphizing drug compounds during granulation with fluidized bed processors [24–30] or high shear granulators [31–34]. Yet, no reports exist on one-step methods for co-amorphous granules.

Feasibility of solvent-free amorphization

In the first part of this study, we explored the feasibility of solvent-free amorphization and pelletization using a high shear granulator. We successfully produced fully amorphized indomethacin-layered pellets simply by mixing indomethacin crystals with microcrystalline cellulose spheres, without applying solvent or heat. Collisions with the spheres pulverized and amorphized the crystals, which then deposited on the surface of the spheres. Based on this, we hypothesized that co-amorphous mixture-layered pellets could also be prepared through one-step amorphization and pelletization. Since earlier studies have achieved co-amorphous mixtures by mechanical activation [16], [22], this approach seems highly promising. Moreover, it provides both economical and sustainable benefits by eliminating the need for solvent and heating.

Previous studies systematically investigated different combinations of indomethacin and amino acids for co-amorphous preparations. The results showed that arginine works as an excellent co-former for indomethacin [18]. This combination produces co-amorphous mixtures with fast dissolution and high physical stability. The reason is that an amorphous salt forms due to strong interactions between acidic indomethacin and basic arginine [35], [36].

Co-amorphous layer pellets

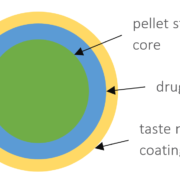

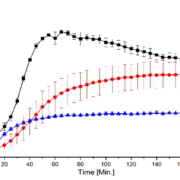

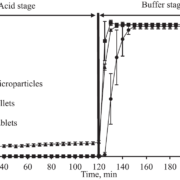

In this study, we aimed to test whether co-amorphous layer pellets can be produced through a one-step amorphization and pelletization process. Therefore, indomethacin was chosen as the model drug and arginine as the co-former. In the first stage, indomethacin crystals were mixed with microcrystalline cellulose spheres of various diameters (140 μm, 195 μm, 275 μm, 414 μm, and 649 μm) at a 1:10 weight ratio using a high shear granulator (TMG1/6, Glatt GmbH, Binzen, Germany). Fully amorphized indomethacin-layered pellets were obtained with 414 μm carriers, while 195 μm carriers resulted in partial amorphization. This difference was most likely caused by the higher impact forces of the larger carriers, which promoted stronger mechanical activation of indomethacin crystals.

To further clarify the role of arginine in amorphization and pelletization, we used smaller cellulose spheres of 195 μm as carriers. Indomethacin and arginine crystals were mixed at different molar ratios (1:1, 2:1, and 3:1). These mixtures were then granulated with cellulose spheres at a 1:10 weight ratio using high shear mixing. The resulting composite particles were analyzed with solid-state and particle characterization methods. In addition, we examined high shear mixing under different jacket temperatures to identify effective co-amorphization conditions. Finally, the physical stability and dissolution behavior of the co-amorphous layer pellets were investigated.

References

[Rades_2022] K. Kondo, T. Rades, 181 (2022) 183-194. doi:10.1016/j.ejpb.2022.11.011

[1] B.C. Hancock, M. Parks, Pharm. Res. 17 (2000) 397-404.

[2] L. Yu, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 48 (2001) 27-42.

[3] L.R. Hilden, K.R. Morris, J. Pharm. Sci. 93 (2004) 3-12.

[4] T. Vasconcelos, S. Marques, J. das Neves, B. Sarmento, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 100 (2016) 85-101.

[5] S. Baghel, H. Cathcart, N.J. O’Reilly, J. Pharm. Sci. 105 (2016) 2527-2544.

[6] R. Laitinen, K. Lobmann, C.J. Strachan, H. Grohganz, T. Rades, Int. J. Pharm. 453 (2013) 65-79.

[7] R.B. Chavan, R. Thipparaboina, D. Kumar, N.R. Shastri, Int. J. Pharm. 515 (2016) 403-415.

[8] S.J. Dengale, H. Grohganz, T. Rades, K. Lobmann, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 100 (2016) 116-125.

[9] S. Janssens, G. Van den Mooter, J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 61 (2009) 1571-1586.

[10] R. Laitinen, K. Lobmann, H. Grohganz, P. Priemel, C.J. Strachan, T. Rades, Int. J. Pharm. 532 (2017) 1-12.

[11] S. Yamamura, H. Gotoh, Y. Sakamoto, Y. Momose, Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 49 (2000) 259-265.

[12] M. Allesø, N. Chieng, S. Rehder, J. Rantanen, T. Rades, J. Aaltonen, J. Control. Release 136 (2009) 45-53.

[13] K. Lobmann, R. Laitinen, H. Grohganz, K.C. Gordon, C. Strachan, T. Rades, Mol. Pharm. 8 (2011) 1919-1928.

[14] Q. Lu, G. Zografi, Pharm. Res. 15 (1998) 1202-1206.

[15] M. Descamps, J.F. Willart, E. Dudognon, V. Caron, J. Pharm. Sci. 96 (2007) 1398-1407.

[16] K. Lobmann, H. Grohganz, R. Laitinen, C. Strachan, T. Rades, Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 85 (2013) 873-881.

[17] G. Kasten, H. Grohganz, T. Rades, K. Lobmann, Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 95 (2016) 28-35.

[18] G. Kasten, K. Lobmann, H. Grohganz, T. Rades, Int. J. Pharm. 557 (2019) 366-373.

[19] A. Teja, P.B. Musmade, A.B. Khade, S.J. Dengale, Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 78 (2015) 234-244.

[20] A. Beyer, L. Radi, H. Grohganz, K. Lobmann, T. Rades, C.S. Leopold, Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 104 (2016) 72-81.

[21] E. Lenz, K.T. Jensen, L.I. Blaabjerg, K. Knop, H. Grohganz, K. Lobmann, T. Rades, P. Kleinebudde, Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 96 (2015) 44-52.

[22] K.T. Jensen, F.H. Larsen, C. Cornett, K. Lobmann, H. Grohganz, T. Rades, Mol. Pharm. 12 (2015) 2484-2492.

[23] B. Demuth, Z.K. Nagy, A. Balogh, T. Vigh, G. Marosi, G. Verreck, I. Van Assche, M.E. Brewster, Int. J. Pharm. 486 (2015) 268-286.

[24] D.B. Beten, K. Amighi, A.J. Möes, Pharm. Res. 12 (1995) 1269-1272.

[25] H.-O. Ho, H.-L. Su, T. Tsai, M.-T. Sheu, Int. J. Pharm. 139 (1996) 223-229.

[26] N. Sun, X. Wei, B. Wu, J. Chen, Y. Lu, W. Wu, Powder Technol. 182 (2008) 72-80.

[27] A. Dereymaker, D.J. Scurr, E.D. Steer, C.J. Roberts, G. Van den Mooter, Mol. Pharm. 14 (2017) 959-973.

[28] A. Dereymaker, J. Pelgrims, F. Engelen, P. Adriaensens, G. Van den Mooter, Mol. Pharm. 14 (2017) 974-983.

[29] T. Oshima, R. Sonoda, M. Ohkuma, H. Sunada, Chem. Pharm. Bull. 55 (2007) 1557-1562.

[30] H.J. Kwon, E.J. Heo, Y.H. Kim, S. Kim, Y.H. Hwang, J.M. Byun, S.H. Cheon, S.Y. Park, D.Y. Kim, K.H. Cho, H.J. Maeng, D.J. Jang, Pharmaceutics 11(3) (2019) 136.

[31] N.S. Trasi, S. Bhujbal, Q.T. Zhou, L.S. Taylor, Int. J. Pharm. X 1 (2019) 100035.

[32] A. Seo, P. Holm, H.G. Kristensen, T. Schæfer, Int. J. Pharm. 259 (2003) 161-171.

[33] T. Vilhelmsen, H. Eliasen, T. Schaefer, Int. J. Pharm. 303 (2005) 132-142.

[34] Y.C. Chen, H.O. Ho, J.D. Chiou, M.T. Sheu, Int. J. Pharm. 473 (2014) 458-468.

[35] K.T. Jensen, L.I. Blaabjerg, E. Lenz, A. Bohr, H. Grohganz, P. Kleinebudde, T. Rades, K. Lobmann, J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 68 (2016) 615-624.

[36] K.T. Jensen, F.H. Larsen, K. Lobmann, T. Rades, H. Grohganz, Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 107 (2016) 32-39.

More information on ASD

Read more about amorphous solid dispersions in our application notes.

ingredient pharm

ingredient pharm

ingredientpharm

ingredientpharm

ingredientpharm

ingredientpharm