Selected Scientific literature

Please, find scientific literature on CELLETS®, MCC spheres. This list is constantly updated and does not claim to be complete. If you are author, scientist or R&D specialist, please submit your present publication to us for improving the visibility.

List – Publications with MCC spheres, 2024

Thesis

Modelling the disintegration of pharmaceutical tablets: integrating a single particle swelling model with the discrete element method

University of Strathclyde, Strathclyde Institute of Pharmacy and Biomedical Sciences, CMAC National Facility, 2024, Thesis identifier T16863

M. Soundaranathan

List – Publications with MCC spheres, 2023

Research article

Paediatric solid oral dosage forms for combination products: Improving in vitro swallowability of minitablets using binary mixtures with pellets

European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences (2023), 187, 106471; doi:10.1016/j.ejps.2023.106471

A. Avila-Sierra, A. Lavoisier, C. Timpe, P. Kuehl, L. Wagner, C. Tournier, M. Ramaioli

Research article

Continuous Manufacturing of Cocrystals Using 3D-Printed Microfluidic Chips Coupled with Spray Coating

Pharmaceuticals (2023), 16(8), 1064; doi:10.3390/ph16081064

A. Kara, D. Kumar 2, A.M. Healy, A. Lalatsa, and D.R. Serrano

Research article

High-Speed Tableting of High Drug-Loaded Tablets Prepared from Fluid-Bed Granulated Isoniazid

Pharmaceuticals (2023), 15(4), 1236; doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics15041236

V. Mohylyuk, and D. Bandere

Research article

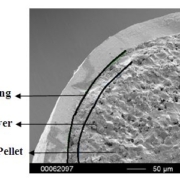

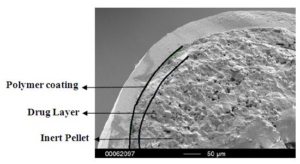

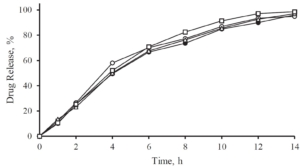

The Effect of Design and Size of the Fluid‑Bed Equipment on the Particle Size‑Dependent Trend of Particle Coating Thickness and Drug Prolonged‑Release Profile

AAPS PharmSciTech (2023) 24, 93. doi:10.1208/s12249-023-02540-9

T. Brezovar, G. Hudovornik, M. Perpar, M. Luštrik, R. Dreu

Research article

Amorphous Solid Dispersions Layered onto Pellets—An Alternative to Spray Drying?

Pharmaceutics (2023) 15(3), 764. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics15030764

M. Neuwirth, S.K. Kappes, M.U. Hartig, K.G. Wagner

Research article

Optimization of Fluidized-Bed Process Parameters for Coating Uniformity and Nutrient-Release Characteristics of Controlled-Release Urea Produced by Modified Lignocellulosic Coating Material

Agronomy (2023) 13(3), 725. doi:10.3390/agronomy13030725

A.M. Ali, B. Azeem, A.M. Alghamdi, K. Shahzad, A. Ahmad Al-Zahrani, M. Imtiaz Rashid, A. Binti Mahpudz, A. Jamil

Research article

Hydrodynamic behaviour of CELLETS® (Ph.Eur./USP) in a spouted bed using image processing method

Particuology (2023), 76, 101-112, doi:10.1016/j.partic.2022.07.009

J. Vanamu, A. Sahoo

List – Publications with MCC spheres, 2022

Research article

Product-Property Guided Scale-Up of a Fluidized Bed Spray Granulation Process Using the CFD-DEM Method

Processes (2022) 10(7), 1291. doi:10.3390/pr10071291

P. Kieckhefen, S. Pietsch-Braune, S. Heinrich

Research article

Influence of In Situ Calcium Pectinate Coating on Metoprolol Tartrate Pellets for Controlled Release and Colon-Specific Drug Delivery

Pharmaceutics (2022) 14(5), 1061. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics14051061

P. Wanasawas, A. Mitrevej, N. Sinchaipanid

Research article

Delamination and wetting behavior of natural hot-melt coating materials

Powder Technology (2022) 404, 117443. doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2022.117443

B.M. Woerthmann, L. Totzauer, H. Briesen

Research article

A systematic approach for assessing the suitability of enteral feeding tubes for the administration of controlled-release pellet formulations

International Journal of Pharmaceutics (2022) 612, 121286. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.121286

F. Karkossa, N. Lehmann, S. Klein

Research article

Spray-freeze-dried lyospheres: Solid content and the impact on flowability and mechanical stability

Powder Technology (2022) 411, 117905. doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2022.117905

A. Rautenberg, A. Lamprecht

Conference proceedings

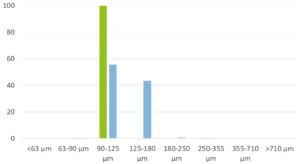

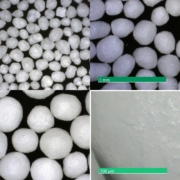

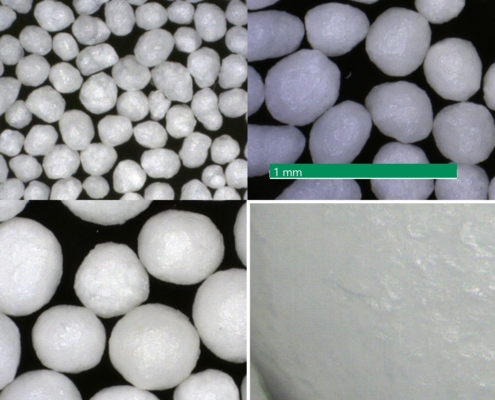

Assessment of the effect of microcrystalline cellulose (MCC) spheres size on the flow via powder rheology

The FORGE, 2022 – pure.qub.ac.uk

V. Mohylyuk, R. Dattani

Research article

Solventless amorphization and pelletization using a high shear granulator. Part II; Preparation of co-amorphous mixture-layered pellets using indomethacin and arginine

European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics (2022) 181, 183-194. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2022.11.011

K. Kondo, T. Rades

Research article

Solventless amorphization and pelletization using a high shear granulator. Part I; feasibility study using indomethacin

European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics (2022) 181, 147-158. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2022.11.010

K. Kondo, T. Rades

Research article

Application of different models to evaluate the key factors of fluidized bed layering granulation and their influence on granule characteristics

Powder Technology (2022), 408:117737. doi: 10.1016/j.powtec.2022.117737

R. Maharjan, S. H. Jeong

Research article

Evaluation of gravitational consolidation of binary powder mixtures by modified Heckel equation

Powder Technology (2022), 408:117729. doi: 10.1016/j.powtec.2022.117729

P. Svačinová, O. Macho, Ž. Jarolímová, M. Kuentz, Ľ. Gabrišová and Z. Šklubalová

Research article

Integrated Purification and Formulation of an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient via Agitated Bed Crystallization and Fluidized Bed Processing

Pharmaceutics (2022), 14(5)1058. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14051058

M. W. Stocker, M. J. Harding, V. Todaro, A. M. Healy and S. Ferguson

List – Publications with MCC spheres, 2021

Research article

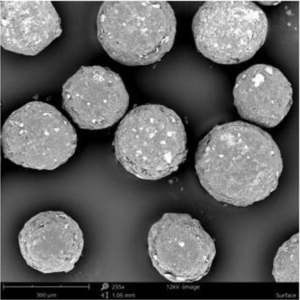

Correlating Granule Surface Structure Morphology and Process Conditions in Fluidized Bed Layering Spray Granulation

KONA Powder and Particle Journal (2021), DOI:10.14356/kona.2022016

M. Orth, P. Kieckhefen, S. Pietsch and S. Heinrich

Research article

Relative bioavailability enhancement of simvastatin via dry emulsion systems: comparison of spray drying and fluid bed layering technology

Eur J Pharm Biopharm (2021), S0939-6411(21)00353-2. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2021.12.004

M. Pohlen, J. Aguiar Zdovc, J. Trontelj, J. Mravljak, M. G. Matjaž, I. Grabnar, T. Snoj and R. Dreu

Research article

A novel method for assessing the coating uniformity of hot-melt coated particles using micro-computed tomography

Powder Technology, Volume 378, Part A, 22 January 2021, Pages 51-59

B.M. Woerthmann, J.A. Lindner, T. Kovacevic, P. Pergam, F. Schmid, H. Briesen

List – Publications with MCC spheres, 2020

Research article

Material specific drying kinetics in fluidized bed drying under mechanical vibration using the reaction engineering approach

Advanced Powder Technology, Volume 31, Issue 12, December 2020, Pages 4699-4713

Soeren E. Lehmann, Tobias Oesau, Alfred Jongsma, Fredrik Innings, Stefan Heinrich

Research article

Simulation of pellet coating in Wurster coaters

International Journal of Pharmaceutics, Volume 590, 30 November 2020, 119931

Hamid Reza Norouzi

Research article

Quantification of swelling characteristics of pharmaceutical particles

International Journal of Pharmaceutics, Volume 590, 30 November 2020, 119903

Mithushan Soundaranathan, Pattavet Vivattanaseth, Erin Walsh, Kendal Pitt, Blair Johnston, Daniel Markl

Short communication

Introduction of the energy to break an avalanche as a promising parameter for powder flowability prediction

Powder Technology, Volume 375, 20 September 2020, Pages 33-41

Žofie Trpělková, Hana Hurychová, Martin Kuentz, Barbora Vraníková, Zdenka Šklubalová

Research article

Easy to Swallow “Instant” Jelly Formulations for Sustained Release Gliclazide Delivery

Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Volume 109, Issue 8, August 2020, Pages 2474-2484

Simmi Patel, Nathan Scott, Kavil Patel, Valentyn Mohylyuk, William J. McAuley, Fang Liu

Research article

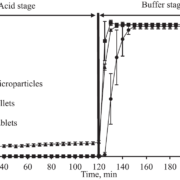

Regulating the pH of bicarbonate solutions without purging gases: Application to dissolution testing of enteric coated tablets, pellets and microparticles

International Journal of Pharmaceutics, Volume 585, 30 July 2020, 119562

Nathan Scott, Kavil Patel, Tariro Sithole, Konstantina Xenofontos, Valentyn Mohylyuk, Fang Liu

Research article

Measuring segregation characteristics of industrially relevant granular mixtures: Part II – Experimental application and validation

Powder Technology, Volume 368, 15 May 2020, Pages 278-285

Alexander M. Fry, Vidya Vidyapati, John P. Hecht, Paul B. Umbanhowar, Julio M. Ottinoa, Richard M. Lueptow

Research article

Non-uniform drug distribution matrix system (NUDDMat) for zero-order release of drugs with different solubility

International Journal of Pharmaceutics, Volume 581, 15 May 2020, 119217

Matteo Cerea, Anastasia Foppoli, Luca Palugan, Alic Melocchi, Lucia Zema, Alessandra Maroni, Andrea Gazzaniga

Research article

Effects of humidity on cellulose pellets loaded with potassium titanium oxide oxalate for detection of hydrogen peroxide vapor in powders

Powder Technology, Volume 366, 15 April 2020, Pages 348-357

Maria H. Kastvig, Cosima Hirschberg, Frans W.J. Van Den Berg, Jukka Rantanen, Mogens L. Andersen

Research article

In-line particle size measurement and process influences on rotary fluidized bed agglomeration

Powder Technology, Volume 364, 15 March 2020, Pages 673-679

Marcel Langner, Ivonne Kitzmann, Anna-Lena Ruppert, Inken Wittich, Bertram Wolf

Research article

Recent advance in delivery system and tissue engineering applications of chondroitin sulfate

Carbohydrate Polymers, Volume 230, 15 February 2020, 115650

Jun Yang, Mingyue Shen, Huiliang Wen, Yu Luo, Rong Huang, Liyuan Rong, Jianhua Xie

Research article

Fixed-bed-column studies for Methylene blue removal by Cellulose CELLETS

Environmental Engineering and Management Journal, Volume 19 (2), March 2020, 269-279

Iulia Nica, Gabriela Biliuta, Carmen Zaharia, Lacramioara Rusu, Sergiu Coseri, Daniela Suteu

Research article

Optimization and tracking of coating processes of pellets with polyvinylpyrrolidone solutions in an acoustic levitator

Powder Technology, Volume 360, 15 January 2020, Pages 1126-1133

Doris L. Wong, Anna-Lena Wirsching, Kai Betz, Andreas Reinbeck, Hans-Ulrich Moritz, Werner Pauer

List – Publications with MCC spheres, 2019

Research article

Measurement of hydrogen peroxide vapor in powders with potassium titanium oxide oxalate loaded cellulose pellets as probes

AAPS PharmSciTech, Volume 21(1):3, 11 Nov 2019

Maria H. Kastvig, Johan P. Bøtker, Ge Ge, Mogens L. Andersen

Research article

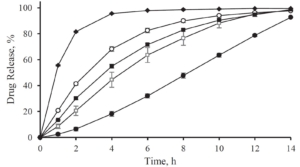

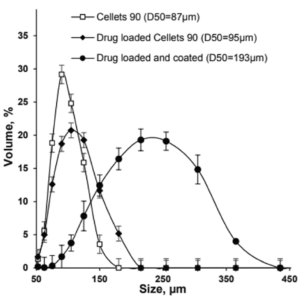

Wurster Fluidised Bed Coating of Microparticles: Towards Scalable Production of Oral Sustained-Release Liquid Medicines for Patients with Swallowing Difficulties

AAPS PharmSciTech, Volume 21(1):3, 11 Nov 2019

Valentyn Mohylyuk, Kavil Patel, Nathan Scott, Craig Richardson, Darragh Murnane, Fang Liu

Research article

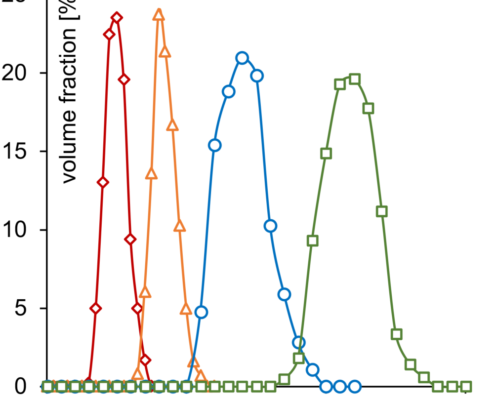

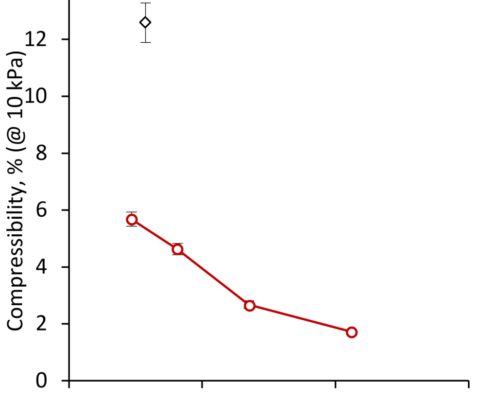

Assessment of the effect of Cellets’ particle size on the flow in a Wurster fluid-bed coater via powder rheology

Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology, Volume 54, December 2019, 101320

Valentyn Mohylyuk, Ioanna Danai Styliari, Dmytryi Novykov, Reiss Pikett, Rajeev Dattani

Research article

Particle electrification in an apparatus with a draft tube operating in a fast circulating dilute spout-fluid bed regime

Particuology, Volume 42, February 2019, Pages 146-153

Wojciech Ludwig

Research article

Development and evaluation of budesonide-based modified-release liquid oral dosage forms

Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology, Volume 54, December 2019, 101273

Federica Ronchi, Antonio Sereno, Maxime Paide, Ismaël Hennia, Pierre Sacré, George Guillaume, Vincent Stéphenne, Jonathan Goole, Karim Amighi

Research article

Evaluation of in-line particle measurement with an SFT-probe as monitoring tool for process automation using a new time-based buffer approach

European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Volume 128, 1 February 2019, Pages 162-170

Theresa Reimers, Jochen Thies, Stefan Dietrich, Julian Quodbach, Miriam Pein-Hackelbusch

Research article

In vitro and sensory tests to design easy-to-swallow multi-particulate formulations

European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Volume 132, 30 April 2019, Pages 157-162

Marco Marconati, Felipe Lopez, Catherine Tuleu, Mine Orlu, Marco Ramaioli

Research article

Numerical study of the hydrodynamics of fluidized beds operated under sub-atmospheric pressure

Chemical Engineering Journal, Volume 372, 15 September 2019, Pages 1134-1153

Sayali Zarekar, Andreas Bück, Michael Jacob, Evangelos Tsotsas

Research article

Solidification of carvedilol loaded SMEDDS by swirling fluidized bed pellet coating

International Journal of Pharmaceutics, Volume 566, 20 July 2019, Pages 89-100

J. Mandić, M. Luštrik, F. Vrečer, M. Gašperlin, A. Zvonar Pobirk

Research article

Quantitative bin flow analysis of particle discharge using X-ray radiography

Powder Technology, Volume 344, 15 February 2019, Pages 693-705

Sanket Bacchuwar, Vidya Vidyapati, Ke-ming Quan, Chen-Luh Lin, Jan D. Miller

Research article

Adjustment of triple shellac coating for precise release of bioactive substances with different physico-chemical properties in the ileocolonic region

International Journal of Pharmaceutics, Volume 564, 10 June 2019, Pages 472-484>

Eva-Maria Theismann, Julia Katharina Keppler, Jörg-Rainer Knipp, Daniela Fangmann, Esther Appel, Stanislav N. Gorb, Georg H. Waetzig, Stefan Schreiber, Matthias Laudes, Karin Schwarz

Research article

The analysis of the influence of the normal restitution coefficient model on calculated particles velocities by means of Eulerian-Lagrangian approach

Powder Technology, Volume 344, 15 February 2019, Pages 140-151

Wojciech Ludwig, PaweƚPłuszka

Research article

Measurement of granule layer thickness in a spouted bed coating process via optical coherence tomography

Powder Technology, Volume 356, November 2019, Pages 139-147

Swantje Pietsch, Anna Peter, Patrick Wahl, Johannes Khinast, Stefan Heinrich

Research article

A novel method of quantifying the coating progress in a three-dimensional prismatic spouted bed

Particuology, Volume 42, February 2019, Pages 137-145

Swantje Pietsch, Finn Ole Poppinga, Stefan Heinrich, Michael Müller, Michael Schönherr, Frank Kleine Jäger

Research article

Development and evaluation of an omeprazole-based delayed-release liquid oral dosage form

International Journal of Pharmaceutics, Volume 567, 15 August 2019, 118416

Federica Ronchi, Antonio, Sereno, Maxime Paide, Pierre Sacré, George Guillaume, Vincent Stéphenne, Jonathan Goole, Karim Amighi

Research article

Influence of separation properties and processing strategies on product characteristics in continuous fluidized bed spray granulation

Powder Technology, Volume 342, 15 January 2019, Pages 572-584

Daniel Müller, Andreas Bück, Evangelos Tsotsas

List – Publications with MCC spheres, 2018

Short communication

Novel production method of tracer particles for residence time measurements in gas-solid processes

Powder Technology, Volume 338, October 2018, Pages 1-6

Swantje Pietsch, Paul Kieckhefen, Michael Müller, Michael Schönherr, Frank Kleine Jäger, Stefan Heinrich

Research article

The effect of administration media on palatability and ease of swallowing of multiparticulate formulations

International Journal of Pharmaceutics, Volume 551, Issues 1–2, 15 November 2018, Pages 67-75

Felipe L. Lopez, Terry B. Ernest, Mine Orlu, CatherineTuleu

Research article

Compressibility and tablet forming ability of bimodal granule mixtures: Experiments and DEM simulations

International Journal of Pharmaceutics, Volume 540, Issues 1–2, 5 April 2018, Pages 120-131

Josefina Nordström, Göran Alderborn, Göran Frenning

Research article

Effects of pharmaceutical processes on the quality of ethylcellulose coated pellets: Quality by design approach

Powder Technology, Volume 339, November 2018, Pages 25-38

Prakash Thapa, Ritu Thapa, Du Hyung Choi, Seong Hoon Jeong

Research article

Euler-Lagrange model of particles circulation in a spout-fluid bed apparatus for dry coating

Powder Technology, Volume 328, 1 April 2018, Pages 375-388

Wojciech Ludwig, Paweł Płuszka

Research article

Inline acoustic monitoring to determine fluidized bed performance during pharmaceutical coating

International Journal of Pharmaceutics, Volume 549, Issues 1–2, 5 October 2018, Pages 293-298

Allan Carter, Lauren Briens

Research article

Sifting segregation of ideal blends in a two-hopper tester: Segregation profiles and segregation magnitudes

Powder Technology, Volume 331, 15 May 2018, Pages 60-67

Mariagrazia Marucci, Banien Al-Saaigh, Catherine Boissier, Marie Wahlgren, Håkan Wikström

Conference abstract

Multiple unit mini-tablets: Content uniformity issues

International Journal of Pharmaceutics, Volume 536, Issue 2, 5 February 2018, Pages 506-507

Anna Kira Adam, Jörg Breitkreutz

Research article

Influence of gas inflow modelling on CFD-DEM simulations of three-dimensional prismatic spouted beds

Powder Technology, Volume 329, 15 April 2018, Pages 167-180

Paul Kieckhefen, Swantje Pietsch, Moritz Höfert, Michael Schönherr, Stefan Heinrich, Frank Kleine Jäger

Research article

A redispersible dry emulsion system with simvastatin prepared via fluid bed layering as a means of dissolution enhancement of a lipophilic drug

International Journal of Pharmaceutics, Volume 549, Issues 1–2, 5 October 2018, Pages 325-334

Mitja Pohlen, Luka Pirker, Matevž Luštrik, Rok Dreu

Review article

Overview of PAT process analysers applicable in monitoring of film coating unit operations for manufacturing of solid oral dosage forms

European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Volume 111, 1 January 2018, Pages 278-292

Klemen Korasa, Franc Vrečer

Research article

On the properties and application of beeswax, carnauba wax and palm fat mixtures for hot melt coating in fluidized beds

Advanced Powder Technology, Volume 29, Issue 3, March 2018, Pages 781-788

M.G. Müller, J.A. Lindner, H. Briesen, K. Sommer, P. Foerst

Research article

Novel hydrophilic matrix system with non-uniform drug distribution for zero-order release kinetics

Journal of Controlled Release, Volume 287, 10 October 2018, Pages 247-256

Matteo Cerea, Alessandra Maroni, Luca Palugan, Marco Bellini, Anastasia Foppoli, Alice Melocchi, Lucia Zema, Andrea Gazzaniga

Research article

Role of plasticizer in membrane coated extended release oral drug delivery system

Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology, Volume 44, April 2018, Pages 231-243

Pinak Khatri, Dipen Desai, Namdev Shelke, Tamara Minko

Research article

Evaluation of pellet cycle times in a Wurster chamber using a photoluminescence method

Chemical Engineering Research and Design, Volume 132, April 2018, Pages 1170-1179

Domen Kitak, Rok Šibanc, Rok Dreu

Research article

Influence of perforated draft tube air intake on a pellet coating process

Powder Technology, Volume 330, 1 May 2018, Pages 114-124

Matevž Luštrik, Rok Dreu, Matjaž Perpar

Research article

Optimising the in vitro and in vivo performance of oral cocrystal formulations via spray coating

European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics, Volume 124, March 2018, Pages 13-27

Dolores R. Serrano, David Walsh, Peter O’Connell, Naila A. Mugheirbi, Zelalem Ayenew Worku, Francisco Bolas-Fernandez, Carolina Galiana, Maria Auxiliadora Dea-Ayuela, Anne Marie Healy

Research article

Mechanics of Pharmaceutical Pellets—Constitutive Properties, Deformation, and Breakage Behavior

Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Volume 107, Issue 2, February 2018, Pages 571-586

Alexander Russell, Rok Šibanc, Rok Dreu, Peter Müller

List – Publications with MCC spheres, 2017

Research article

Production of composite particles using an innovative continuous dry coating process derived from extrusion

Advanced Powder Technology, Volume 28, Issue 11, November 2017, Pages 2875-2885

Fanny Cavaillès, Romain Sescousse, Alain Chamayou, Laurence Galet

Research article

Determination of the release mechanism of Theophylline from pellets coated with Surelease®—A water dispersion of ethyl cellulose

International Journal of Pharmaceutics, Volume 528, Issues 1–2, 7 August 2017, Pages 345-353

Jurgita Kazlauske, Maria Margherita Cafaro, Diego Caccavo, Mariagrazia Marucci, Gaetano Lamberti, Anna Angela Barba, Anette Larsson

Research article

In-line monitoring of multi-layered film-coating on pellets using Raman spectroscopy by MCR and PLS analyses

European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics, Volume 114, May 2017, Pages 194-201

Jin Hisazumi, Peter Kleinebudde

Research article

Analysis of pellet coating uniformity using a computer scanner

International Journal of Pharmaceutics, Volume 533, Issue 2, 30 November 2017, Pages 377-382

Rok Šibanc, Matevž Luštrik, Rok Dreu

Research article

Modeling of particle velocities in an apparatus with a draft tube operating in a fast circulating dilute spout-fluid bed regime

Powder Technology, Volume 319, September 2017, Pages 332-345

Wojciech Ludwig, Daniel Zając

Research article

UV imaging of multiple unit pellet system (MUPS) tablets: A case study of acetylsalicylic acid stability

European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics, Volume 119, October 2017, Pages 447-453

Anna Novikova, Jens M. Carstensen, Thomas Rades, Claudia S. Leopold

Research article

New hybrid CPU-GPU solver for CFD-DEM simulation of fluidized beds

Powder Technology, Volume 316, 1 July 2017, Pages 233-244

H.R. Norouzi, R. Zarghami, N. Mostoufi

Research article

A top coating strategy with highly bonding polymers to enable direct tableting of multiple unit pellet system (MUPS)

Powder Technology, Volume 305, January 2017, Pages 591-596

Frederick Osei-Yeboah, Yidan Lan, Changquan Calvin Sun

Research article

Synthesis and melt processing of cellulose esters for preparation of thermoforming materials and extended drug release tablets

Carbohydrate Polymers, Volume 177, 1 December 2017, Pages 105-115

Sanna Virtanen, Riku Talja, Sauli Vuoti

Research article

Downstream drug product processing of itraconazole nanosuspension: Factors influencing drug particle size and dissolution from nanosuspension-layered beads

International Journal of Pharmaceutics, Volume 524, Issues 1–2, 30 May 2017, Pages 443-453

Johannes Parmentier, En Hui Tan, Ariana Low, Jan Peter Möschwitzer

List – Publications with MCC spheres, 2016

Research article

In-line particle size measurement and agglomeration detection of pellet fluidized bed coating by Spatial Filter Velocimetry

Powder Technology, Volume 301, November 2016, Pages 261-267

Dimitri Wiegel, Günter Eckardt, Florian Priese, Bertram Wolf

Research article

Effect of formulation variables on oral grittiness and preferences of multiparticulate formulations in adult volunteers

European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Volume 92, 20 September 2016, Pages 156-162

Felipe L. Lopez, Alexandra Bowles, Mine Orlu Gul, David Clapham, Terry B. Ernest, Catherine Tuleu

Research article

Micropellet-loaded rods with dose-independent sustained release properties for individual dosing via the Solid Dosage Pen

International Journal of Pharmaceutics, Volume 499, Issues 1–2, 29 February 2016, Pages 271-279

Eva Julia Laukamp, Klaus Knop, Markus Thommes, Joerg Breitkreutz

Research article

Multivariate calibration of the degree of crystallinity in intact pellets by X-ray powder diffraction

International Journal of Pharmaceutics, Volume 502, Issues 1–2, 11 April 2016, Pages 107-116

Krisztina Nikowitz, Attila Domján, Klára Pintye-Hódi, Géza Regdon jr.

Research article

Towards improving quality of video-based vehicle counting method for traffic flow estimation

Signal Processing, Volume 120, March 2016, Pages 672-681

Yingjie Xia, Xingmin Shi, Guanghua Song, Qiaolei Geng, Yuncai Liu

Conference abstract

Multiple-unit orodispersible mini-tablets

International Journal of Pharmaceutics, Volume 511, Issue 2, 25 September 2016, Page 1128

Anna Kira Adam, Christian Zimmer, Stefan Rauscher, Jörg Breitkreutz

Research article

Asymmetric distribution in twin screw granulation

European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics, Volume 106, September 2016, Pages 50-58

Tim Chan Seem, Neil A. Rowson, Ian Gabbott, Marcelde Matas, Gavin K. Reynolds, AndyIngram

Research article

Measurement of particle concentration in a Wurster coater draft tube using light attenuation

Chemical Engineering Research and Design, Volume 110, June 2016, Pages 20-31

R. Šibanc, I. Žun, R. Dreu

List – Publications with MCC spheres, 2015

Research article

Two-dimensional particle shape analysis from chord measurements to increase accuracy of particle shape determination

Powder Technology, Volume 284, November 2015, Pages 25-31

D. Petrak, S. Dietrich, G. Eckardt, M. Köhler

Research article

Passive acoustic emission monitoring of pellet coat thickness in a fluidized bed

Powder Technology, Volume 286, December 2015, Pages 172-180

Taylor Sheahan, Lauren Briens

Research article

Tabletability Modulation Through Surface Engineering

Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Volume 104, Issue 8, August 2015, Pages 2645-2648

Frederick Osei-Yeboah, Changquan Calvin Sun

Research article

Cellulose CELLETS as new type of adsorbent for the removal of dyes from aqueous media

Environmental Engineering and Management Journal, Volume 14, Issue 3, March 2015, Pages 525-532

Daniela Suteu, Gabriela Biliuta, Lacramioara Rusu, Sergiu Coseri, Gabriela Nacu

Research article

Formulation and process optimization of multiparticulate pulsatile system delivered by osmotic pressure-activated rupturable membrane

International Journal of Pharmaceutics, Volume 480, Issues 1–2, 1 March 2015, Pages 15-26

Sheng-Feng Hung, Chien-Ming Hsieh, Ying-Chen Chen, Cheng-Mao Lin, Hsiu-O Ho, Ming-Thau Sheu

Research article

Dry Coating Characterization of Coverage by Image Analysis: Methodology

Procedia Engineering, Volume 102, 2015, Pages 81-88

Olivier Lecoq, Fredj Kaouach, Alain Chamayou

Research article

Passive acoustic emissions monitoring of the coating of pellets in a fluidized bed—A feasibility analysis

Powder Technology, Volume 283, October 2015, Pages 373-379

Taylor Sheahan, Lauren Briens

List – Publications with MCC spheres, 2014

Research article

A New Apparatus for Real‐Time Assessment of the Particle Size Distribution of Disintegrating Tablets

Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Volume 103, Issue 11, November 2014, Pages 3657-3665

Julian Quodbach, Peter Kleinebudde

Research article

In-line spatial filtering velocimetry for particle size and film thickness determination in fluidized-bed pellet coating processes

European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics, Volume 88, Issue 3, November 2014, Pages 931-938

Friederike Folttmann, Klaus Knop, Peter Kleinebudde, Miriam Pein

Research article

On-line monitoring of fluid bed granulation by photometric imaging

European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics, Volume 88, Issue 3, November 2014, Pages 879-885

Ira Soppela, Osmo Antikainen, Niklas Sandler, Jouko Yliruusi

Research article

Application properties of oral gels as media for administration of minitablets and pellets to paediatric patients

International Journal of Pharmaceutics

Volume 460, Issues 1–2, 2 January 2014, Pages 228-233

Anna Kluk, Malgorzata Sznitowska

Research article

In-line monitoring of pellet coating thickness growth by means of visual imaging

International Journal of Pharmaceutics, Volume 470, Issues 1–2, 15 August 2014, Pages 8-14

Nika Oman Kadunc, Rok Šibanc, Rok Dreu, Boštjan Likar, Dejan Tomaževič

Research article

Optical microscopy as a comparative analytical technique for single-particle dissolution studies

International Journal of Pharmaceutics, Volume 469, Issue 1, 20 July 2014, Pages 10-16

Sami Svanbäck, Henrik Ehlers, Jouko Yliruusi

Research article

Formulation of itraconazole nanococrystals and evaluation of their bioavailability in dogs

European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics, Volume 87, Issue 1, May 2014, Pages 107-113

Lieselotte De Smet, Lien Saerens, Thomas De Beer, Robert Carleer, Peter Adriaensens, Jan Van Bocxlaer, Chris Vervaet, Jean PaulRemon

Research article

Global monitoring of fluidized-bed processes by means of microwave cavity resonances

Measurement, Volume 55, September 2014, Pages 520-535

Johan Nohlert, Livia Cerullo, Johan Winges, Thomas Rylander, Tomas McKelvey, Anders Holmgren, Lubomir Gradinarsky, Staffan Folestad, Mats Viberg, Anders Rasmuson

List – Publications with MCC spheres, 2013

Research article

Water-mediated solid-state transformation of a polymorphic drug during aqueous-based drug-layer coating of pellets

International Journal of Pharmaceutics, Volume 456, Issue 1, 1 November 2013, Pages 41-48

Andres Lust, Satu Lakio, Julia Vintsevits, Jekaterina Kozlova, Peep Veski, Jyrki Heinämäki, Karin Kogermann

Research article

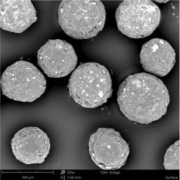

Preparation and characterization of controlled-release doxazosin mesylate pellets using a simple drug layering-aquacoating technique

Journal of Pharmaceutical Investigation (2013), 43:333–342. doi: 10.1007/s40005-013-0077-0

H. A. Hazzah, M. A. EL-Massik, O. Y. Abdallah & H. Abdelkader

Research article

Development of high drug loaded pellets by Design of Experiment and population balance model calculation

Powder Technology, Volume 241, June 2013, Pages 149-157

Florian Priese, Bertram Wolf

Research article

Particle sizing measurements in pharmaceutical applications: Comparison of in-process methods versus off-line methods

European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics, Volume 85, Issue 3, Part B, November 2013, Pages 1006-1018

Ana F.T. Silva, Anneleen Burggraeve, Quenten Denon, Paul Van der Meeren, Niklas Sandler, Tom Van Den Kerkhof, Mario Hellings, Chris Vervaet, Jean Paul Remon, João Almeida Lopes, Thomas De Beer

Research article

Physical properties of pharmaceutical pellets

Chemical Engineering Science, Volume 86, 4 February 2013, Pages 50-60

Rok Šibanc, Teja Kitak, Biljana Govedarica, StankoSrčič Rok Dreu

Research article

Continuous pellet coating in a Wurster fluidized bed process

Chemical Engineering Science, Volume 86, 4 February 2013, Pages 87-98

N. Hampel, A. Bück, M. Peglow, E. Tsotsas

Research article

Study of the recrystallization in coated pellets – Effect of coating on API crystallinity

European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Volume 48, Issue 3, 14 February 2013, Pages 563-571

Krisztina Nikowitz, Klára Pintye-Hódi, Géza Regdon Jr.

Research article

The influence of rolling friction on the shear behaviour of non-cohesive pharmaceutical granules – An experimental and numerical investigation

European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Volume 49, Issue 2, 13 May 2013, Pages 241-250

Ann-Sofie Persson, Göran Frenning

Research article

Characteristics of pellet flow in a Wurster coater draft tube utilizing piezoelectric probe

Powder Technology, Volume 235, February 2013, Pages 640-651

Matevž Luštrik, Rok Šibanc, Stanko Srčič, Matjaž Perpar, Iztok Žun, Rok Dreu

Research article

Estimating coating quality parameters on the basis of pressure drop measurements in a Wurster draft tube

Powder Technology, Volume 246, September 2013, Pages 41-50

Matjaž Perpar, Matevž Luštrik, Rok Dreu, Stanko Srčič, Iztok Žun

Research article

Influence of Non-Water-Soluble Placebo Pellets of Different Sizes on the Characteristics of Orally Disintegrating Tablets Manufactured by Freeze-Drying

Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Volume 102, Issue 6, June 2013, Pages 1786-1799

Ulrike Stange, Christian Führling, Henning Gieseler

List – Publications with MCC spheres, 2012

Research article

A density-based segmentation for 3D images, an application for X-ray micro-tomography

Analytica Chimica Acta, Volume 725, 6 May 2012, Pages 14-21

Thanh N. Tran, Thanh T. Nguyen, Tofan A. Willemsz, Gijsvan Kessel, Henderik W. Frijlink, Kees van der Voort Maarschalk

Research article

Attrition and abrasion resistance of particles coated with pre-mixed polymer coating systems

Powder Technology, Volume 230, November 2012, Pages 1-13

G. Perfetti, F. Depypere, S. Zafari, P. van Hee, W.J. Wildeboer, G. M. H. Meesters

Research article

New spout-fluid bed apparatus for electrostatic coating of fine particles and encapsulation

Powder Technology, Volume 225, July 2012, Pages 52-57

Roman G. Szafran, Wojciech Ludwig, Andrzej Kmiec

Research article

Particle size and packing characterization by diffuse light transmission

Particuology Volume 10, Issue 5, October 2012, Pages 619-627

Henrik Ehlers, Jyrki Heinämäki, Jouko Yliruusi

Research article

Dry Powder Coating in a Modified Wurster Apparatus

Procedia Engineering, Volume 42, 2012, Pages 437-446

W. Ludwig, R.G. Szafran, A. Kmiec, J. Dziak

Research article

Attrition strength of water-soluble cellulose derivative coatings applied on different core materials

Powder Technology, Volume 222, May 2012, Pages 71-79

Katarzyna Nienaltowska, Frédéric Depypere, Giacomo Perfetti, Gabrie M.H. Meesters, Frederik Ronsse, Jan G. Pieters, Koen Dewettinck

Research article

An experimental evaluation of the accuracy to simulate granule bed compression using the discrete element method

Powder Technology, Volume 219, March 2012, Pages 249-256

Ann-Sofie Persson, Göran Frenning

List – Publications with MCC spheres, 2011

Research article

Dry particle high coating of biopowders: An energy approach

Powder Technology, Volume 208, Issue 2, 25 March 2011, Pages 378-382

S. Otles, O. Lecoq, J. A. Dodds

Research article

A density based segmentation method to determine the coordination number of a particulate system

Chemical Engineering Science, Volume 66, Issue 24, 15 December 2011, Pages 6385-6392

Thanh T. Nguyen, Thanh N. Tran, Tofan A. Willemsz, Henderik W. Frijlink, Tuomas Ervasti, Jarkko Ketolainen, Kees van der Voort Maarschalk

Research article

Study of the preparation of a multiparticulate drug delivery system with a layering technique

Powder Technology, Volume 205, Issues 1–3, 10 January 2011, Pages 155-159

Krisztina Nikowitz, Péter Kása Jr., Klára Pintye-Hódi, Géza Regdon Jr.

Research article

Effect of annealing time and addition of lactose on release of a model substance from Eudragit® RS coated pellets produced by a fluidized bed coater

Chemical Engineering Research and Design, Volume 89, Issue 6, June 2011, Pages 697-705

Ulrich M. Heckötter, Anette Larsson, Pornsak Sriamornsak, Mont Kumpugdee-Vollrath

Research article

Suspension pellet layering using PVA–PEG graft copolymer as a new binder

International Journal of Pharmaceutics, Volume 412, Issues 1–2, 30 June 2011, Pages 28-36

L. Suhrenbrock, G. Radtke, K. Knop, P. Kleinebudde

Research article

In-line particle sizing for real-time process control by fibre-optical spatial filtering technique (SFT)

Advanced Powder Technology, Volume 22, Issue 2, March 2011, Pages 203-208

Petrak Dieter, Dietrich Stefan, Eckardt Günter, Köhler Michael

Research article

Flowability of surface modified pharmaceutical granules: A comparative experimental and numerical study

European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Volume 42, Issue 3, 14 February 2011, Pages 199-209

Ann-Sofie Persson, Göran Alderborn, Göran Frenning

List – Publications with MCC spheres, 2010

Research article

Labscale fluidized bed granulator instrumented with non-invasive process monitoring devices

Chemical Engineering Journal, Volume 164, Issues 2–3, 1 November 2010, Pages 268-274

Jari T. T. Leskinen, Matti-Antero H. Okkonen, Maunu M. Toiviainen, Sami Poutiainen, Mari Tenhunen, Pekka Teppola, Reijo Lappalainen, Jarkko Ketolainen, Kristiina Järvinen

Research article

X-ray micro tomography and image analysis as complementary methods for morphological characterization and coating thickness measurement of coated particles

Advanced Powder Technology, Volume 21, Issue 6, November 2010, Pages 663-675

Giacomo Perfetti, Elke Van de Casteele, Bernd Rieger, Willem J. Wildeboer, Gabrie M.H. Meesters

Research article

Granule size distribution of tablets

Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Volume 99, Issue 4, April 2010, Pages 2061-2069

Satu Virtanen, Osmo Antikainen, Heikki Räikkönen, Jouko Yliruusi

Research article

New insights into segregation during tabletting

International Journal of Pharmaceutics, Volume 397, Issues 1–2, 15 September 2010, Pages 19-26

S. Lakio, S. Siiriä, H. Räikkönen, S. Airaksinen, T. Närvänen, O. Antikainen, J.Yliruusi

Short communication

Can encapsulation lengthen the shelf-life of probiotic bacteria in dry products?

International Journal of Food Microbiology, Volume 136, Issue 3, 1 January 2010, Pages 364-367

F. Weinbreck, I. Bodnár, M.L. Marco

Research article

Evaluation of in-line spatial filter velocimetry as PAT monitoring tool for particle growth during fluid bed granulation

European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics, Volume 76, Issue 1, September 2010, Pages 138-146

A. Burggraeve, T. Van Den Kerkhof, M. Hellings, J.P. Remon, C. Vervaet, T. De Beera

List – Publications with MCC spheres, 2009

Research article

Impact of polymers on dissolution performance of an amorphous gelleable drug from surface-coated beads

European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Volume 37, Issue 1, 11 April 2009, Pages 1-10

Chon gFan, Rashmi Pai-Thakur, Wantanee Phuapradit, Lin Zhang, Hung Tian, Waseem Malick, Navnit Shah, M. Serpil Kislalioglu

Short communication

Raman spectroscopic investigation of film thickness

Polymer Testing, Volume 28, Issue 7, October 2009, Pages 770-772

T. Sovány, K. Nikowitz, G. Regdon Jr., P. Kása Jr., K. Pintye-Hódi

Research article

In vivo evaluation of the vaginal distribution and retention of a multi-particulate pellet formulation

European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics, Volume 73, Issue 2, October 2009, Pages 280-284

Nele Poelvoorde, Hans Verstraelen, Rita Verhelst, Bart Saerens, Ellen De Backer, Guido Lopes dos Santos Santiago, Chris Vervaet, Mario Vaneechoutte, Fabienne De Boeck, Luc Van Borteld, Marleen Temmerman, Jean-Paul Remon

Research article

Modulating pH-independent release from coated pellets: Effect of coating composition on solubilization processes and drug release

European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics, Volume 72, Issue 1, May 2009, Pages 111-118

Simon Ensslin, Klaus Peter Moll, Hendrik Metz, Markus Otz, Karsten Mäder

Research article

Dry Particle High-Impact Coating of Biopowders: Coating Strength

Particulate Science and Technology, Volume 27(4), 2009

S. Ötles, O. Lecoq, J. A. Dodds

Book

Formulation and Analytical Development for Low-Dose Oral Drug Products

John Wiley & Sons , inc. (2009), ISBN 978-0-470-05609-7

Jack Zheng (Editor)

List – Publications with MCC spheres, 2008 and earlier

Research article

Attrition strength of different coated agglomerates

Chemical Engineering Science, Volume 63, Issue 5, March 2008, Pages 1361-1369

B. van Laarhoven, S.C.A. Wiers, S.H. Schaafsma, G.M.H. Meesters

Research article

Direct Drug Loading into Preformed Porous Solid Dosage Units by the Controlled Particle Deposition (CPD), a New Concept for Improved Dissolution Using SCF-Technology

Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Volume 97, Issue 10, October 2008, Pages 4416-4424

Ragna S. Wischumerski, Michael Türk, Martin A. Wahl

Research article

Optimisation of an enteric coated, layered multi-particulate formulation for ileal delivery of viable recombinant Lactococcus lactis

European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics, Volume 69, Issue 3, August 2008, Pages 969-976

Nele Poelvoorde, Nathalie Huyghebaert, Chris Vervaet, Jean-Paul Remon

Research article

Dynamic rearrangement of disulfide bridges influences solubility of whey protein coatings

International Dairy Journal, Volume 18, Issue 5, May 2008, Pages 566-573

René Floris, Igor Bodnár, Fanny Weinbreck, Arno C. Alting

Research article

New insight into modified release pellets – Internal structure and drug release mechanism

Journal of Controlled Release, Volume 128, Issue 2, 4 June 2008, Pages 149-156

Simon Ensslin, Klaus Peter Moll, Kurt Paulus, Karsten Mäder

Research article

Development of an enteric-coated, layered multi-particulate formulation for ileal delivery of viable recombinant Lactococcus lactis

European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics, Volume 61, Issue 3, October 2005, Pages 134-141

Nathalie Huyghebaert, An Vermeire, Pieter Rottiers, Erik Remaut, Jean Paul Remon

Research article

Evaluation of extrusion/spheronisation, layering and compaction for the preparation of an oral, multi-particulate formulation of viable, hIL-10 producing Lactococcus lactis

European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics, Volume 59, Issue 1, January 2005, Pages 9-15

Nathalie Huyghebaert, An Vermeire, Sabine Neirynck, Lothar Steidler, Eric Remaut, Jean Paul Remon

Research article

Liquid absorption capacity of carriers in the food technology

Powder Technology, Volume 134, Issue 3, 30 September 2003, Pages 201-209

Heidi Lankes, Karl Sommer, Bernd Weinreich

ingredientpharm

ingredientpharm

ingredientpharm

ingredientpharm

Ingredientpharm

Ingredientpharm

glatt.com

glatt.com